EXPL123 - Course Title Goes Here

Module x.x - Gay-Lussac's Gas Law

Throughout this module, you may use the on-screen arrows to navigate between sections. When you are ready to begin, click on the "begin" button below.

EXPL123 - Course Title Goes Here

Module x.x - Gay-Lussac's Gas Law

Learning Objectives

Using Gay-Lussac's gas law, you should be able to describe the change that occurs in the initial versus the final temperature, and/or pressure of a gas, either through numeric calculations or statements of cause and effect. You must score 80% or higher on a formal assessment in order to successfully complete this module.

About This Module

Keep the following things in mind as we work through this module:

- We will use Kelvin (marked as K) for our units of temperature. Using Kelvin is required for these calculations.

- Converting Fahrenheit (°F) to Kelvin: Take the temperature in Fahrenheit and add 459.67 to it, then multiply that result by 5/9 (if not using a scientific calculator, you can first multiply by 5 and then divide by 9).

- Converting Celcius (°C) to Kelvin: Just add 273.15 to the temperature in Celcius to get the equivalent temperature in Kelvin.

- We will use Pounds per Square Inch (abbreviated as PSI) for units of pressure in our examples. Any units for pressure can be used, as long as they stay the same throughout the problem.

- It might help to keep a calculator close by — any standard calculator will work.

Background

Hey there! I'm Kayla, and I'll be your guide for this module. Together, we'll be looking at Gay-Lussac's Gas Law and how it affects our world on a daily basis. Don't believe me? Let's take a look at some examples.

Background

Have you ever noticed when opening a bottle of soda that's been in the fridge for a while, it barely lets out any "hiss"? In contrast, when you open one that's been sitting on the table, it lets out a large, very audible hissing sound.

Without opening the bottle, what factors might be different between when the bottle is in the fridge versus when it's outside the fridge? And beyond that, what determines the strength of the hissing sound when you open the bottle?

Background

How about a personal example? Last week, I used a tire pressure gauge to measure the air in my tires before a road trip. They all measured around 32psi before I left. After a while of driving, I used the gauge again to make sure my tires weren't losing any air, but to my surprise the gauge read 34psi!

I didn't stop to add any air, and tires definitely don't "suck in" air on their own. They're at a higher pressure than the outside air, so if anything, the air would want to escape. How could the pressure gauge read higher than when I left in the morning?

Background

It seems like all of these examples have something to do with a gas: The carbon dioxide in the soda and the air in the tires.

How do we know what's changing in each situation, though? It sounds like we need to set up an experiment and gather some data. I have just the friend who can help, too! Head to the next section when you're ready to meet him and observe the results.

Running Our Experiments: The Soda

Hi! I'm Professor Parker, Kayla's friend, and I'll be running the experiments for us so we can observe the results. Click on the image below to start the experiment.

Running Our Experiments: Car Tires

Now we're getting somewhere. We have two experiments with similar outcomes, but we'll still look at Kayla's road trip example for good measure. When you're ready, click to begin.

Analyzing the Results

There's definitely something going on with both the temperature and pressure of the gases in these experiments. Can you guess what it is?

Drawing a Conclusion

You're well on your way to mastering Gay-Lussac's Law! You were correct in stating that temperature and pressure are correlated, and that as temperature increases, so does pressure (and vice versa).

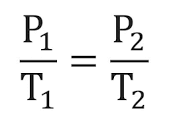

In fact, Gay-Lussac's Law states that the changes in temperature and pressure are directly proportional, meaning that they both increase or decrease by the same amount. This means the formula for calculating the change can be written as:

where T1 is the starting temperature, T2 is the final temperature, P1 is the starting pressure, and P2 is the final pressure.

Keep in mind, though, that this law only works if the volume of the gas involved stays constant. Since the two environments we looked at kept the gas contained, the volume did not change and we could use this law.

How about we look at some new examples? When you're ready, press the "Continue" button to work through a couple more practice scenarios on your own.

Practice Exercises

Below are a few practice exercises for you to practice what you've seen so far in this module. You'll be presented with a couple example situations and must select the best answer to the question that's posed from a list of options.

Exercise 1

A student removes an airtight container of gas from a refrigerated storage at -10°F (249.81K) and places it on the table, allowing it to warm up to a room temperature of 68°F (293.15K). The pressure gauge on the container read 10PSI when he removed it from storage.

At room temperature, which is the most likely reading for the pressure gauge? (Hint: using the formula for Gay-Lussac's Law would give you the exact answer, but it is not required.)

Practice Exercises

Exercise 2

An engineer is designing a pressure relief valve for a normally airtight gas container that should open if the pressure gets too high, in this case 200PSI. In its normal operating environment, the temperature of the room the gas container is located in measures about 300K, and the normal operating pressure inside the gas container is 100PSI.

Use Gay-Lussac's formula to calculate the temperature which the gas would need to reach before the safety system kicks in.

Practice Exercises

Exercise 3

You put some food in a pressure cooker and close the lid. Before you start the cooking process, you press on the pressure relief valve on the top of the unit, and nothing happens. After several minutes of cooking, you press the valve again and hear a hissing sound, and determine this is the sound of pressure being released from inside the unit.

Which statement best uses Gay-Lussac's law to describe what happened?